I intimated to you last Sunday that, in view of the fact

that the centenary of the birth of George MacDonald fell on

Wednesday of last week, I intended to take as my subject here

this evening "His Message as a Preacher." I then added, "Great

as his merits may be as a poet and prose-writer, they are even

greater as a preacher. Over his own day and generation he exercised

a wonderful influence; and for years to come Huntly will be

a place of pilgrimage to many who feel that they owe to him

the best impulses of their lives." Since I made that intimation

I have been interested to find that I am not alone in this estimate

of George Macdonald's work. John Malcolm Bulloch, who contributed

an article upon him on Wednesday last, speaks of him as "a most

persuasive preacher." While Professor Grierson, I find, in

a criticism and appreciation which appeared in the Aberdeen

University Review for November is quite emphatic on the point

that preaching was his forte - that only as a preacher can he

be understood. Let me quote merely one sentence. "It was not

for fame," he says, "that George MacDonald wrote, but . to deliver

a spiritual message to his nation and generation. . . . A preacher

he was, and as a preacher you must read him, or leave him alone."

I make no apology, therefore, for choosing his message as my

theme tonight. I consider, indeed, that we should fail in our

duty as a church if we allowed the centenary of his birth to

pass without seeking to understand what it was which he sought

to tell us, or without trying to catch something of the inspiration

which makes the story of his life so remarkable and so beautiful.

For as Mr. Bulloch truly remarks - "Between his private life

and his literature, there is perfect unity - he regarded both

as an expression of all things under and beyond the sun."

His message, let it be said at once, is both negative and positive

- negative as to many of the dogmas commonly regarded as inviolate

in his day; and positive as to the great facts of Christian

teaching which have been the heritage of believers in every

generation - faith, hope, love of Christ and love of one's fellow-men.

His message has sometimes been characterized as vague. One writer,

for example, while admitting that all George MacDonald's books

reveal "deep spiritual instincts," yet speaks of "the nebulosity

of his mental atmosphere and his inability for sustained thought."

But that is obviously an unfair criticism. He certainly formulated

no system (we may thank Heaven for the fact), and sometimes

no doubt he stressed aspects of his teaching to the exclusion

of other aspects which are equally precious (what preacher does

not occasionally make that mistake?): but whether he is destroying

dogmas that offend or upholding dogmas that appeal, he invariably

finds the conscience of his reader. He "gets home," as we say,

and no preacher who does that can be dismissed as "nebulous."

George MacDonald of course suffered, as all preachers of his

day and generation suffered, by having to work through much

that was false before he could reach the true. The passage from

the negative to positive was in his case both logical in sequence

and chronological in time; and for that reason we cannot do

better than deal with his negative or destructive teaching first,

and then pass on to his positive or constructive teaching.

First, then, let us consider his negative teaching. It was negative,

as I have stated, as to many of the dogmas commonly regarded

as inviolate in his day. For keep in mind that during the formative

period of George MacDonald's life, a very narrow and a very

rigid type of orthodoxy held sway in his Huntly home. Mr. George

Cowie, who became minister of the Congregational Church in 1771

(the "Missionar Kirk" as it was called then) was a strict Calvinist.

He preached a noble faith, and he did a noble work; and far

and wide he made converts. Among them was Isabella Robertson,

George MacDonald's grandmother, who was a young girl of fifteen

when Mr. Cowie began his Huntly ministry. Unfortunately, the

faith which he preached had all the faults of its virtue. It

was unbending in its sternness to sin, and uncompromising in

its treatment of sinners. In short, it produced, as it could

only produce, either saints or hypocrites.

Now Isobel Robertson undoubtedly ranked among the saints. She

is the "Mrs. Falconer" described by George MacDonald with such

lifelike accuracy in the third of his Huntly novels; and no

one, whose sympathies are true and whose moral vision is sound,

can read that story without loving Mrs. Falconer. To say so,

however, is not to blind oneself to her obvious deficiencies;

and what those were may be gathered from the fact that all worldly

pleasures was in her eyes "anathema," and that she burned her

grandson's fiddle in the kitchen fire lest it should prove a

snare to his soul. As a boy, indeed, George MacDonald regarded

her with awe and fear. She was the embodiment of "the missionar's

religion"; and for him that religion seemed to be summed up

in perpetual maxims of restraint. The advice he invariably received,

going or coming, was "Noo, be douce."

Happily, his father had a broader outlook, and afforded him

a very different idea of religion both in theory and in practice.

George MacDonald, Senior, shared the grandmother's faith - he

was a deacon indeed (as was also his brother James), in the

Congregational Church, but the Celtic blood in him was strong,

and his instincts were altogether finer and tenderer. Deep sorrows,

moreover, and the hard blows of circumstance had done much to

modify his Calvinism. He loved his children; and in return George

MacDonald loved his father. He loved him as much as he feared

his grandmother. His father's portrait he has also given us,

for he is the "David Elginbrod" of the story of that name, and

one has only to contrast the two pictures - Mrs. Falconer on

one hand and David Elginbrod on the other - to clearly realize

the religious influences that moulded the poet's early life.

The truth is that when he left home, and had to face the problems

of life for himself, he knew only three types of religion -

his father's, which he loved; his grandmother's, which he respected

but feared (his appreciation was a thing of later life); and

the type of religion represented by that large class of hangers-on

of an evangelical faith who, unable to rise to its heights,

yet ape its manners, and bring it into contempt. It was that

last type against which he inveighed, denouncing it in bitter

sarcasm and fierce invective.

For inevitably he was driven to the conclusion that the narrowness

of the creed created it, and the creed therefore shared his

condemnation. To his mind religion should have nothing to do

with creed. Religion must be a passion - passion which brings

a man into vital contact with God Himself. "My quarrel," he

represents David Elginbrod as saying, "wi a' thae words, an

airguments, an' seemilies, as thae ca' them - is just this -

they haud a puir body at airm's length oot ower frae God Himsel'.

They raise sic a mist an stour a' aboot Him..Gin fowk wad be

persuaded to speak a word or two to God Him lane, the loss in

my opinion, wad be unco' sma' an' the gain very great." For

the same reason he had little or no faith in a "conversion"

which was based on mere belief. The process seemed to him altogether

too mechanical, and the results for the life of the so-called

converted altogether too negative. "Till we begin to learn,"

he says (and again we seem to catch his father's accents), "that

the only way to serve God in any real sense of the word is to

serve our neighbor, we may have knocked at the wicket-gate,

but I doubt if we have got one foot across the thresh-hold of

the Kingdom."

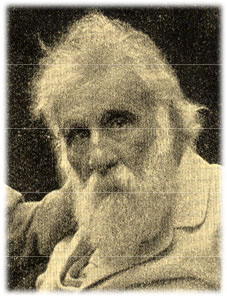

George MacDonald in 1901

George MacDonald in 1901 |

Teaching like that must have descended upon the Calvinists of

the past century like a tonic visitation. In Scotland it certainly

made its immediate appeal. Nay, it swept across the religious

life of the country like a health-giving breeze. It was almost

the first brush with reality which the religious community had

experienced since the days of Robert Burns; and it may fairly

be claimed that George MacDonald, like Burns, did not a little

to emancipate Scotland from the thralldom of an outworn creed,

and to make its practice somewhat more consistent with its preaching.

But we can well understand how he roused criticism; and how

in the hearts of the "tince guid" there was no slight dismay.

In nonconformist England indeed he was completely misunderstood;

and the Congregational Church at Arundel, which he had elected

to serve, thought that his teaching verged on the blasphemous.

Even before he had been there two years, criticism of his orthodoxy

began to be freely circulated; and when he added to his sins

the publication of a small collection of the songs of Novalis

(a book having a German origin and therefore tainted with German

theology!) his cup of iniquity was full. In the freer atmosphere

of an established church, where he might have stated his serious

convictions without being penalized, it is just possible that

George MacDonald might have found a useful niche in the ministry.

At a later date, indeed, prompted by the intense yet human preaching

of F. D. Maurice, he joined the communion of the Church of England.

But the deacons at Arundel effectually put a stop to George

MacDonald's pulpit career. They first reduced his salary and

then they intimated to him that his preaching was not acceptable

(they had no idea that one among them, the latchet of whose

shoes they were not worthy to unloose); and therefore it was

no longer possible, as George MacDonald wrote to his father,

"to stand toward them in this position - to be regarded as their

servant rather than Christ's."

It must be borne in mind, however, that such treatment never

shook his faith. The very reverse. Six months later we find

him writing to his father, "Till my heart is like Christ's great

heart, I cannot fully know what He meant. . . . You must not

be surprised if you hear that I am not what is called 'getting

on.' Time will show what use the Father will make of me." On

this negative aspect of his teaching let me, indeed, merely

add this - that important as was the service which he rendered

by it to the cause of true religion, in his own eyes it was

of the least moment. The eternal verities were what moved his

soul. Far on in life we find him summing up that early experience

in a letter which leaves no doubt on this point - "With the

faith to be found in the old Scottish manse," he writes, "I

have a true sympathy. With many of the forms gathered around

that faith . I have none. At a very early date I began to cast

them from me; but all the time my faith in Jesus, as the son

of the Father of men and the Saviour of us all, has been growing..

Do not suppose that I believe in Jesus because so-and-so is

said about Him in a book. I believe in Him, because He is Himself.

. The Bible is to me the most precious thing in the world just

because

it tells me the story of Jesus." All of George MacDonald's negations

indeed were dictated by incontrovertible facts. Even Calvinism

he did not reject. As Mr. Chesterton says, he was himself an

"optimistic Calvinist." He simply rejected caricatures of that

teaching - interpretations which in the pure crucible of his

own thought and life seemed to him to dishonour God and conscience.

Reprinted

from Volume 45 of Wingfold, a magazine celebrating the

works of George MacDonald. Information on this fine publication

may be obtained from Barbara Amell at 5925 SE 40th,

Portland, OR 97202, USA, and at the website: http://www.wingfold.net.

Back

to Top